A cascade of wage garnishment notices is set to descend upon millions of American households, signaling not just personal financial turmoil but a potential shockwave to the entire U.S. economy. As the federal government resumes its most aggressive collection tactics on defaulted student loans, experts are sounding the alarm over a confluence of factors that could push an already strained consumer base past its breaking point. The resumption of these payments, compounded by the recent elimination of critical affordability programs, has created a perfect storm of financial pressure. This situation moves beyond individual hardship, raising a critical question about the nation’s economic stability: with over 40 million Americans holding student debt, is the system now so vast and fragile that its unraveling could drag the broader economy down with it? The answer may lie in the delicate balance between federal policy, household budgets, and the consumer spending that fuels national growth.

The Human Cost of Default

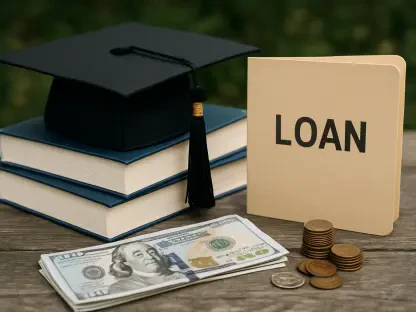

For millions of borrowers already grappling with financial instability, the looming threat of wage garnishment represents a devastating blow. Betsy Mayotte, President of the Institute of Student Loan Advisors, characterizes this collection method as one that “hits where it hurts,” a punitive measure that often seizes a larger portion of a person’s income than a standard monthly payment would. This approach can quickly plunge a struggling household into an even more precarious financial state, creating a vicious cycle of debt and desperation. While effective from a collector’s standpoint in “getting people’s attention,” its real-world impact is often counterproductive, punishing those who are genuinely unable to pay rather than those who are simply unwilling. The consequence is not just a reduced paycheck but a cascade of financial crises, from an inability to afford rent and groceries to the potential for bankruptcy, all stemming from a debt originally taken on to pursue educational and economic advancement.

However, the severe consequences of default are not an unavoidable fate for those facing delinquency. Proactive engagement offers a pathway out of the crisis, a point strongly emphasized by Winston Berkman-Breen, Legal Director with Protect Borrowers. He advises against inaction, highlighting several established routes to resolve a default status and avoid the harsh reality of garnishment. Options like loan rehabilitation or consolidation can restore a loan to good standing, effectively wiping the slate clean on a default. Furthermore, enrolling in an income-driven repayment plan remains a critical tool, as these programs can adjust monthly payments to a more manageable level based on a borrower’s actual earnings. The overarching consensus from experts is clear: communication is paramount. By contacting their loan servicers, borrowers can navigate these complex but available options, transforming a situation of potential financial ruin into a manageable repayment journey and reclaiming their financial stability before it is forcibly taken from them.

A System in Conflict

The national conversation surrounding student loan defaults is characterized by a fundamental and deep-seated conflict in perspective. The Department of Education, through statements from officials like Under Secretary Nicholas Kent, firmly champions a position of personal responsibility. This viewpoint frames the issue in stark terms of legal and fiscal obligation, asserting that “The law is clear: if you take out a loan, you must pay it back.” This perspective casts the government’s aggressive collection efforts as a necessary measure to protect taxpayer interests and maintain the “fiscal health” of the student loan portfolio. In this narrative, default is an individual failure to uphold a commitment. In stark contrast, many borrower advocates and legal experts argue that this view overlooks systemic failures. Winston Berkman-Breen contends that landing in default is often “a failure of the system,” not a moral lapse, especially as more affordable repayment options have been progressively taken offline, leaving borrowers with fewer viable paths to stay current.

Ultimately, this debate over individual versus systemic failure may be a distraction from the core issue that experts universally agree on: the exorbitant and continually escalating cost of higher education itself. Betsy Mayotte identifies student loans as merely “the symptom of the problem,” with the actual disease being the runaway inflation in college tuition. Data from the Education Data Initiative confirms this alarming trend, showing that the cost of college has more than doubled in the 21st century, far outpacing wage growth and general inflation. This reality forces students and their families into a difficult position where taking on substantial debt feels like the only option. Mayotte strongly advises families to conduct a rigorous “cost-benefit analysis” before borrowing, warning against accumulating large loans for careers with limited earning potential. She advocates for more financially prudent pathways, such as starting at a community college, a strategy that could mitigate the debt burden for the 70 percent of students who end up changing their major or school.

Policy Shifts and Rising Economic Risks

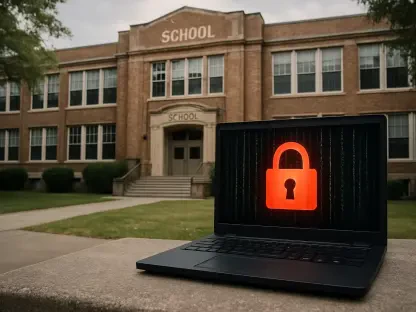

Recent policy changes have dramatically amplified the financial risks for millions of borrowers, moving the student debt issue from a chronic problem to a potential acute crisis. The most significant of these shifts is the Department of Education’s decision to eliminate the Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan. This program, established under the Biden administration, was a lifeline for many, offering significantly lower monthly payments calculated based on discretionary income. For some, it even reduced payments to zero. Its abrupt removal forces borrowers to select other, often more expensive, repayment plans, leading to a sudden and substantial increase in their monthly household expenses. This is not a minor adjustment; for families who had carefully budgeted around the affordable SAVE payments, this change represents a financial shock that can destabilize their entire economic foundation, forcing difficult choices between paying their student loans and affording other essential needs.

This sudden increase in financial obligations is occurring within a precarious economic context, creating what many experts describe as a perfect storm. Betsy Mayotte predicts that the U.S. is now heading toward a “historically high default rate for student loans,” directly linking this forecast to the elimination of the SAVE plan. The timing is particularly perilous, as this new financial burden on households coincides with a period where other economic supports, such as healthcare subsidies, may also be disappearing. The cumulative effect is a powerful squeeze on the American consumer. This convergence of rising costs and diminishing support systems is what raises the specter of macroeconomic fallout. When a significant portion of the population is forced to divert hundreds of dollars more per month toward debt, it inevitably means less money is available for consumer spending, savings, and investment, a scenario that has economists deeply concerned about a broader economic slowdown.

The Tipping Point for a Broader Downturn

The sheer scale of the student debt crisis provides the necessary context for understanding its potential to trigger a recession. Over 40 million Americans, roughly one in every eight people, are currently carrying student loan debt. Within this group, a staggering 5 million are already in default, defined as having failed to make a payment for at least 270 days. This is not a burden confined to recent graduates; data dismantles that misconception, revealing that half of all borrowers are over the age of 30, and a quarter are over 45. The government’s plan to resume wage garnishments will be implemented in phases, starting with an initial group of 1,000 borrowers and expanding monthly, ensuring a slow but steady increase in financial pressure across the country. The problem is particularly acute in states like North Carolina, which holds the nation’s seventh-highest average debt load, underscoring the geographically widespread nature of this burgeoning crisis.

The direct link between this widespread financial distress and a potential economic recession lies in the fundamentals of consumer spending, which serves as the primary engine of the U.S. economy. As Winston Berkman-Breen noted, the societal benefits of financially stable citizens are vast; when people are not crushed by debt, they have the discretionary income to spend at local businesses, start their own enterprises, and make career choices that benefit their communities. The aggressive push for repayment, especially after the removal of affordable plans, directly threatens this economic activity. As millions of households are forced to divert significant portions of their income to service debt, a corresponding reduction in consumer spending is inevitable. This collective pullback, multiplied across millions of borrowers, creates a powerful drag on the economy, potentially reducing demand, slowing growth, and tipping the nation into a recessionary cycle driven not by a market crash, but by the crippling weight of educational debt.

Navigating the Aftermath

The aggressive renewal of collections and the simultaneous dismantling of key relief programs had created a precarious economic landscape. The national dialogue had shifted from debating the causes of student debt to confronting the immediate consequences of policies that placed millions of households under unprecedented financial strain. It became clear that the financial well-being of a substantial portion of the population was inextricably linked to the stability of the entire economy. This realization forced a difficult reckoning for policymakers, financial institutions, and educational leaders, who were left to grapple with the aftermath and seek sustainable solutions. The crisis had underscored a fundamental truth: a system that saddles generations with unmanageable debt was not just a personal burden but a systemic risk to national prosperity, prompting a critical re-evaluation of how higher education was financed and valued in America.